Semper Volans. What does it mean? It is a Latin phrase meaning, “Always Flying.” This might be fairly self-explanatory, but I wanted to explain in length why I chose this moniker because it has multiple applications. This will be heavily influenced by aviation, for pilots are always flying, as it were, but I wanted to extend it to other applications and show a connection to how someone can apply it to how they live in general. I’m not a doctor or an expert and I’m not offering advice. I’m offering a reflection that someone might find helpful. It’s the framework that I try to use and it seems to have helped me. There is also a connection to St. Paul that bears expounding on, which I will describe by way of concluding this reflection.

To begin answering why I chose “always flying” I wanted to begin by explaining the literal meaning, which will be a little technical. I think those not familiar with aviation will find it useful and it will be easier to explain my later points with this foundation. I’m going to work principally off the Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge and The Airplane Flying Handbook published by the FAA since they describe the concepts for beginner pilots, which will be enough to serve the purpose here.

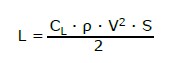

The equation for lift is as follows:  CL is the coefficient of lift, rho is the air density, v is the velocity, S is the surface area of the wings, and all that is divided by 2. Punch those numbers in, and you get lift. But all that is too complicating for our purpose here, so I’m going to oversimplify it. To do that, let’s review the three laws of motion from Sir Isaac Newton and the venturi effect of Bernoulli.

CL is the coefficient of lift, rho is the air density, v is the velocity, S is the surface area of the wings, and all that is divided by 2. Punch those numbers in, and you get lift. But all that is too complicating for our purpose here, so I’m going to oversimplify it. To do that, let’s review the three laws of motion from Sir Isaac Newton and the venturi effect of Bernoulli.

Newton declared these three things to be true:

- An object at rest remains at rest until acted upon.

- Force=Mass times Acceleration: acceleration acts inversely proportional to mass and directly proportional to applied force: basically this is what accounts for speed/direction.

- For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

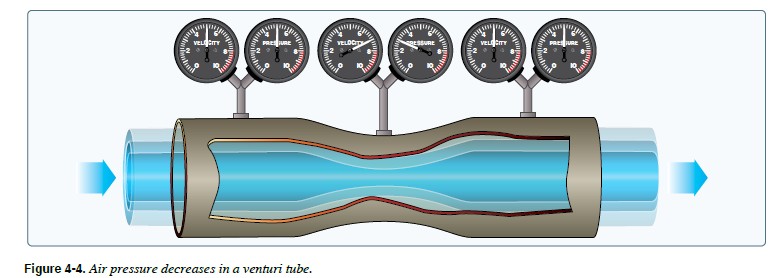

Bernoulli demonstrated that as the velocity of a fluid increases, the pressure decreases. This is shown best in a venturi tube.

As air is pushed through the tube, the constriction forces it to accelerate, which causes a drop in pressure. As it passes the constriction, the speed decreases and the pressure increases again.

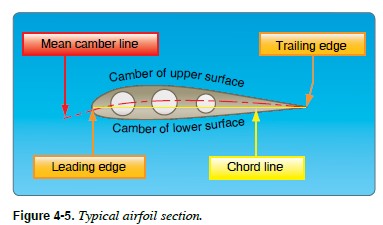

An airplane can fly primarily because of the wing. This surface is generally thin and has curvature to it, or camber.

It is thicker at one end and thinner and the other, and it is more rounded on the top side and flatter on the bottom. Wings, also known as airfoils, play around with various thicknesses and cambers and shapes to generate different kinds of lift (i.e. some are for supersonic flight, others for slow flight, etc). For our purpose, the wing is a standard wing the FAA would have us learn. It is thicker in the leading edge, and tapers down to the trailing edge, and it has more camber on the top of the wing than on the bottom of the wing. When the plane is resting, the wing is resting. No lift is generated because the object is at rest. This is Newton’s first law. Next, to generate a force, we have Newton’s second law. This is accomplished by playing four forces of flight off of each other (thrust, weight, lift, drag). To get the plane to move, thrust has to overcome drag. To get airborne, lift has to overcome weight. Lastly, when a force is applied there’s a reaction, which takes us to Bernoulli’s principle.

Flight occurs when lift overcomes weight. It does this through thrust from the engine and airfoil design. When an engine applies thrust, air begins to move over the wing. The more thrust/velocity, the more airflow over the wing, and the faster the air flows. Eventually, enough airflow generates lift. This is accomplished by the camber of the wing. Air hits the wing and parts like the Red Sea. Air goes over the top of the wing, and air flows under the wing. Like in Bernoulli’s venturi tube, the mass of the airflow needs to be the same at the end of the tube as in the beginning, or in this case, at the end of the wing. This is where camber comes into play. The curvature on the topside of the wing forces the air to travel the same distance but faster as the bottomside of the wing, which is flatter. This increase in acceleration causes Bernoulli’s drop in pressure, which means that the top of the wing has less pressure than the bottom of the wing. What’s the result? Newton’s Third Law kicks in. The reaction to the drop in pressure above is an increase in pressure below. This increase in pressure on the bottomside of the wing is lift.

Once airflow over the wings is sufficient, the pressure under the wing continues to push the wing up, keeping it airborne. Once this process is started, it is typically self-sustaining. That is, it is “at rest” until a force is applied to cause it to change. As long as airflow continues over the wing, lift is generated and the airplane will fly.

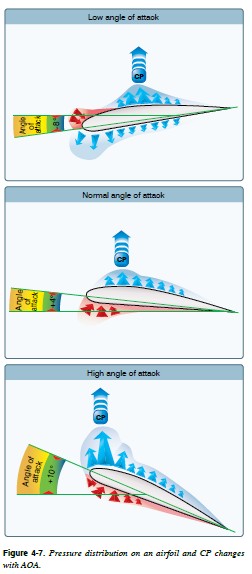

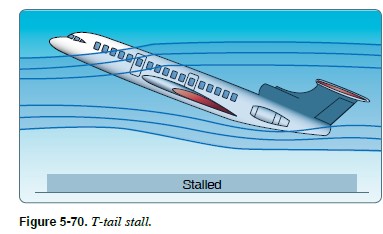

This process is controlled by two things: speed, and, more importantly, angle of attack. Speed gets lift going and there’s a minimum speed for flight to begin, but the most important aspect for a pilot to keep in mind is what’s referred to as Angle of Attack (AOA). AOA determines how much lift is generated by the wings. AOA is the angle of the wing’s cord line (mean center of the wing) relative to the oncoming wind. More AOA = more lift (and usually a slower airspeed). As long as airflow continues over the wing above this minimum speed, the plane will fly. But, it has a limit. This limit is called the Critical Angle of Attack. When this limit is exceeded, the plane will stall — meaning the lift process is broken and there is no longer constantly moving air over the wing generating that high pressure point under the wing (i.e. it drops out of the sky). The wing can only be brought up so high in relation to the wind before the airflow over the wing breaks off and tumbles away. Essentially, the wing acts like a dam preventing airflow from streaming over the wing.

All is not lost, however. Angle of Attack is typically controlled by the ability to move the nose up or down, that is, a pilot’s pitch attitude. As long as he can move the nose and reduce the angle of the wings against the oncoming wind, the air will begin flowing over the wings again, and the stall is recovered. Lift begins self-generating again, and the plane resumes flying. Airspeed also factors into this. Typically, higher AOA’s mean slower airspeeds, and slower airspeeds typically mean less airflow over the wings, so a pilot has to delicately manage these things to keep his plane flying. But it is important to note that an airplane can stall at any attitude and airspeed, but only one critical angle of attack. Speed is important, but that angle of attack is most significant. Typically, there is a correlation between slower speed and needing a higher angle of attack, so the two usually go hand in hand, but that’s keeping it very simple. An experienced aviator, and a prudent one, will keep both in check.

When an aviator achieves this balance, he is flying. As long as he is flying, he must continue flying. He cannot let his ship exceed this critical angle of attack at any time, and he must not get too slow. As long as he does this, his plane will conduct him safely. After these basics, his primary tasks are fuel management and making sound judgments about weather and other hazards. But he doesn’t have to be afraid for lift. The plane wants to fly. There are outside forces that can affect flight, which he must be watchful for. The first is turbulence which can rock the airplane out of equilibrium or stress the airframe if it is severe enough. He has to watch for icing, which is very bad for lift; and he needs to watch for his own maneuvering — so that he doesn’t cause his plane to fail. In all things, however, he has to keep his cool and keep flying. This brings us to the next topic: resignation.

Resignation is when the pilot mentally stops flying. When he mentally quits flying, he physically quits flying, and eventually the plane will do so as well. This freeze/quitting is extremely hazardous because it puts outside forces in control of his ship rather than himself. The aviator must fly and not be flown. How many crashes have happened because the pilot gave up and stopped flying! If a ship is going to go down, or if it seems like it, the aviator must fly it all the way through regardless of what the outcome might be. He must never quit. If it crashes, it crashes with him flying, but how often a ship is saved because he never quit and was always flying.

So how does all this apply to life? Life is like a plane flying to its destination. It has start-up, taxi, flight, descent, and landing. Simply put, we have birth, growth, adult life, old age, and death. There are many external factors that will affect this flight: mechanical issues, turbulence, diversions, weather, delays, other planes, our own good or bad decisions, etc. Sometimes we are alone, sometimes we have a crew, sometimes we have passengers. Sometimes we get lost or nervous or tired. But, we have to keep flying. If the pilot doesn’t, his ship will crash, and depending on circumstances, others will crash with/because of him. So how does a person avoid succumbing to pressures of life and keep flying? First, he knows himself and accepts his circumstances. Second, he assesses his crew and passengers. Third, he makes a sound plan. Fourth, he flies his plan and continually assesses the progress as unexpected risks arise. If necessary, he diverts; sometimes he holds for a while; sometimes he has to refuel or rest — but he learns to be patient. Overreaction and rashness often lead to mistakes and crashes.

Often, among the most critical things a pilot does is the prep work he does on the ground. Before you begin an endeavor, do you do your research? Do you assess the risks and the environment you will be in? Who are you working with? Cavalier pilots make rash judgments. Cavalier people ruin other lives because they don’t take the time to prep. They have no care for others or their ship. They are not aviators. They could never fly well because they have no respect or humility. So it is with life. Life is bumpy; it is joyful; thrilling; fatiguing; full of anxiety; stressful; lonely; sorrowful; hopeful; expectant; pleasant; dull; repetitive. We have to be patient and disciplined and prudent. We have to make sure that no matter, we keep flying. If we stall, if we break that lift, we risk crashing. Crashing sometimes ends well if a pilot takes back control, but it is fatal if it gets the best of him or if he applies the wrong correction. If you keep pulling up in a stall to try to get it to climb, you will crash faster. If your only plan is to survive the crash, you need to re-work the plan, because we should never gamble on surviving a crash.

Whatever our circumstance or place in life, we have to remember that we don’t live just for ourselves. We have a sphere that belongs to us. It starts with family and branches out to friends, then work, then the local community, then to the nation, then to strangers elsewhere. We can’t be helpful to others if we can’t hold ourselves up. We have to take-off and keep ourselves going so others can rely on us. This is risky, and will involve many mistakes, but it also is necessary to live. Flying is inherently risky, but it sharpens our edge, reminds us to respect mortality, gives us a top-down perspective, and broadens our horizons.

This takes us then to St. Paul. St. Paul’s connection to ‘always flying’ is his metaphor of running the race. St. Paul discourses on athletes preparing to win a race for a very perishable crown, and the lengths they go to try to win one. Yet, St. Paul reminds us that they strive for something somewhat foolish, but that we have an imperishable crown to win, and to make matters worse we spend less effort trying to achieve this crown than the athlete does the laurel crown. He admonishes us to put the same effort into getting this crown. He reminds us that the race is a marathon, not a sprint. This is very revealing, because typically flying is the same way. If we rush to begin, we won’t get very far. If you sprint to start a marathon you’ll run out of strength and breath. This means that we have to do a lot of training. It also means that we have to participate in the race — we have to actually run it. We have to put ourselves out in the field, and along the way encourage others. We can’t do this if we just jump right in. We need training and thorough preparation. Heaven is worth it, St. Paul warns, so we have to forego some pleasures to achieve this, or we’ll enjoy our time on earth and spend an eternity suffering.

This, finally is the tie in to ‘always flying’ and more specifically to ‘angle of attack’. We have to plan for the kind of flight we need to make, which might include multiple stops, plans for diversions, gaining cargo and losing cargo, gaining and losing passengers, having a crew-member (a spouse, typically), maybe flying alone. We have to plan for this accordingly. It also means that we conduct the flight accordingly. Just like the marathon runner doesn’t start off by sprinting, we can’t be so earnest to achieve heaven that we angle ourselves too high and stall. Yes, we’ll produce more lift low to the ground, but we won’t be able to sustain it. We will stall. It is just like Jesus’s parable about the seed. We would sprout up like a weed and immediately die for lack of roots. The good seed has good roots and takes its time. It balances its angle of attack.

St. Pier Giorgio Frassati’s motto was “Aim High” (Verso l’alto in Italian). He loved climbing mountains before his death resulting from his unwavering care for the poor. He loved to aim high, but he knew how to pace himself. Climbing a mountain can take days. We need to aim high. That is the reason for flying: to reach out and touch the face of God, as it were. But if we are like Icarus and defy our limits we will plummet to the earth. So we need to measure and gauge our angle of attack. The lower the angle of attack, the less lift, but a steady flight. High angles of attack will be a slower flight, but more aggressive climb. Sometimes we have to skirt the limit of that angle of attack and risk stalling, but masterfully control it so we gain the maximum gain in altitude and lift to avoid hitting an obstacle, or to overcome a task, but we have use that maneuver sparingly and only after we’ve mastered our aircraft. In life, we have to do the same thing. Sometimes we have to be ambitious. Sometimes we have to be aggressive and take a great risk, but it needs to be measured and controlled — it can’t be beyond our ability or resources or support structure. We slowly build our endurance and master ourselves like the runner slowly builds his endurance for the long race. There will be many setbacks and frustrations. Pilots are used to frequently having to deal with maintenance. But they never give up. They keep preparing so that when it is time to fly again, they are ready to go. The primary point is that they keep going. They don’t stop and give up. They pivot, they wait, they study, they find a different way. Sometimes you might feel like you are hanging on by a thread, but don’t let go, because no matter how thin the thread, as long as you are hanging on, you are still in the fight, but you lose if you let go. A pilot can just let go and let his plane get away from him, but he doesn’t. He keeps flying, even it is on margins from time to time. So chase after heaven, aim high, achieve a dream, but watch that angle of attack.